Cover of “Entangled Minds” by Dean Radin. Paraview Pocket Books, New York, 2006.

When I was a kid, I saw little monsters in my bedroom. No one seemed to react when I said as much, though. Most kids see monsters. Actually, it’s probably a little weird for a kid not to see scary stuff in the dark. But if you do, your parents simply tell you what you’re seeing is not real. They might have to keep telling you for a few weeks, months, maybe years, but eventually you’ll stop seeing them, and you’ll grow up to be a normal adult. You’ll go to school, get a job, get married, have kids and tell those kids the little monsters they see aren’t real. If you don’t keep the cycle going, your kids could grow up to be adults who see monsters, and adults who see monsters don’t have it easy when it comes to things like getting a job and finding a partner. So this continual process—this shaping of consensual reality—is good and healthy. Except for one potential little problem—if there ever are real monsters, we won’t be able to see them. We’d be blind to them—not eye blind, but brain blind. And that’s the problem Lucas, the hero of Mantis, has. Even though he can see everything that’s in plain sight—which, as we saw in the previous post, is actually a remarkable genius—he still only sees what his brain accepts as part of consensual reality. It’s this weakness—a weakness that all well-adapted humans possess—that the enemies in Mantis prey upon.

Dean Radin, an award winning scientist who has devoted his career to the study of psychic phenomenon, covers how this brain blindness happens in his bestselling book Entangled Minds. The phenomenon at work is something called latent inhibition, which, as Radin puts it, “refers to an unconscious brain process that degrades our ability to pay attention to stimuli that have had no consequences in the past.” He goes on:

Imagine, for example, that Pavlov’s dogs were exposed to ringing bells without being fed. The dogs will quickly learn to ignore ringing bells because those sounds had no meaningful consequence (i.e. no association with food). Now, Pavlov decides to train the same dogs to salivate whenever they hear a bell by ringing the bells and feeding them. Unfortunately, these dogs had already learned to ignore bells, so they’re going to have a hard time unlearning the old association. Dogs that hadn’t previously heard the irrelevant bells will quickly learn to salivate. This “hard time unlearning” is due to latent inhibition.

That’s what Lucas is up against in Mantis—unlearning the reality he’s been taught all his life to believe in. And that’s no easy feat.

The phenomenon of latent inhibition strikes Lucas hard after he lands in Lisbon just as the Nazis storm through Belgium. In the excerpt below, Lucas, who has just seen the Black Suits kidnap his P. I. partner Olivia, seeks the help of Nick Cap, a Frenchman who seems to know the way to help Lucas.

Half a mile up the slope, I spot a sign for the Hotel Baleia hanging on a slim building tucked between two restaurants. I charge through the lobby, huffing, and ask the concierge for Nick Cap. He calls Nick, says a few words in a foreign language and then hangs up and tells me in broken English Nick’s room number.

Seconds later, I’m standing in a dingy hallway, banging on Nick’s door. He opens it swiftly, a pile of clothes balanced on his palm.

“The Black Suits just kidnapped Olivia,” I say.

“Oh, Lucas, I am sorry.” He steps inside his tiny room and places the clothes into an open suitcase on his bed.

“Are they going to kill her?”

“Explain what happened.”

After I relay the story, he says, “I do not know, Lucas. They could have killed her on the street. They did not. That is good—for now. They only kill if they have to, so it depends if they decide in the end that her death is necessary or not.”

“Where are they taking her?”

“I imagine they will take her to their closest headquarters.”

“Where’s that?”

“I do not know.” He closes the halves of his suitcase together. “If I knew, I would go there.”

“You have to help me find it.”

He lifts his suitcase off the bed onto the floor beside him. “Lucas, I was just about to leave for Casablanca to find the Black Suits.”

“We have to find Olivia first.”

He stares at me with his good eye. “Tell me, Lucas, when your father went missing, what did you think happened?”

“Nick, we don’t have time for this now—I need your help fast.”

“I need you to answer the question first.”

“I had no idea what happened.”

“But there were books, your grandfather’s books that pointed to the answer—is that not so?”

“Nick, please—”

“You saw the books, didn’t you?”

“I saw the books, yes.”

“But you never considered the possibility of other worlds, other dimensions.”

I let out a breath. The clock is ticking. “No sane person does.”

“It is not a question of sanity, Lucas. It is a question of what is real, what is truth. When you think of sanity, you miss things. You missed where your father went. You miss who these Black Suits are. You think you can fight them with a gun and regular bullets. You discovered the truth the hard way—you lost Olivia because of your closed mind.”

My teeth crunch together. “You asked for my father’s watch for some magic bullets, what the hell was I supposed to think?”

“You were supposed to open your mind. I am not, what you call, a snake-oil salesman. I offered you a necessary bargain. The universe works by balance, by bargain, by trade—like the laws of thermodynamics, but at the deepest, metaphysical level. Your grandfather knew about that. There is no… what you call free lunch in this world, or any world, Lucas. Your father’s watch for the method to kill your father’s killer—that was the trade. Without it, even my gold bullets would be no better than what you shot from your gun today.”

“I should have listened to you, yes. I’m sorry. I want to trade for those gold bullets now.”

“You need more than my bullets, Lucas. You need to open your mind. You possess a certain genius—a great memory with extraordinary powers of perception, just like your father and your grandfather. But you are blind, still—by certain prejudices, by certain preconceived notions of the world.”

“I saw my bullets disappear into that bastard’s face. My mind is open now.”

“It is not. And until it is, you’re not ready. You want to rush, Lucas. I understand, but that won’t help you get Olivia back. Your father rushed too. ’e did not wait for me to teach him all I know. He went to the Perisphere without me. He was too impatient. Maybe I could have done more to warn your father, but I will not let you make the same mistake.”

“Then help me get ready, help me open my mind.”

“Okay, Lucas, describe the Black Suit’s face.”

“Gaunt. Sunken pale cheeks. Small dark eyes.”

He shakes his head. “That is what a closed mind sees. You must first understand that as human beings, we perceive everything through five senses. Personally, I believe we have other senses. But whatever you believe, it is true we always filter out a large portion of what we perceive. There is simply too much data. As a Nomi, you, fortunately, do not have this particular limitation. Your brain has the capability to cope with a great deal of information. ’owever, you suffer, as most humans do, from another factor. And that, Lucas, is that we tend to accept only information which conforms to our preconceived notions of the world, shaped by science, by culture, by fear. Children see all manner of strange things—ghosts and so on—and when they report these things to adults we tell them they’re not real. We shape the reality of the child to the acceptable norms. In time, the child learns to filter out whatever does not fit the norms. You must rid yourself of the prejudices you have, of what you expect to see when you see a Black Suit.”

“What should I have seen?”

He pulls a piece of paper from an inside pocket of his jacket and unfolds it on the bed. It’s a pen-and-ink rendition of a revolting monster, a black creature oozing slime that looks partly humanoid and partly like a praying mantis. It has claw-like appendages like Olivia described and its triangular head, with two massive hypnotically dark eyes, tapers to a terrifying chaos of saw-edged mandibles.

“This is what the Black Suits really are, Lucas,” Nick is saying. “Dictyoptera—a unique, supernatural species. Like other creatures in the order of dictyoptera, such as the praying mantis, camouflage is their defense mechanism, but with these dictyoptera, the camouflage is super advanced. A technology unknown to man. It is bullet-proof also—against normal bullets.”

I look at Nick, can’t speak. I can tell he sees the recognition on my face.

“You see something familiar here, don’t you?”

I hesitate before saying, “I’ve never seen anything like this. But I’ve seen hundreds of black mantises in these visions I get at night. I’ve had them for years back in my world and a few here too. Some of the insects are regular sized, some larger.”

Nick’s eyes light up—finally he is getting somewhere with me. “At night when you dream, Lucas, your mind is open. It shows you the deeper reality of the world, things your conscious mind has filtered out. Your subconscious mind must have detected these dictyoptera somewhere and then shown you in your dreams a representation of what they really are with images of mantises. That makes sense, because a mantis insect is the closest norm you have for these dictyoptera. It is a good sign that you’ve had these dreams, Lucas. It gives me hope that your mind could be opened.”

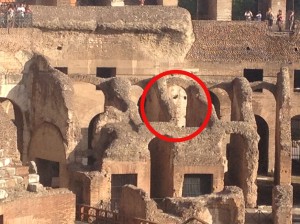

How’s this for eerie? I was in Rome recently indulging in wine, cheese and gelato and scouting locations for one of the Mantis sequels. One of the places I checked out was the Colosseum. While walking around the upper gallery, I was debating in my head whether or not to set a particular sequence in the ruins of the ancient amphitheater. In the midst of my hemming and hawing I turned my head and saw this stone Mantis face. So yeah, maybe the Colosseum will find its way into one of the novels.

How’s this for eerie? I was in Rome recently indulging in wine, cheese and gelato and scouting locations for one of the Mantis sequels. One of the places I checked out was the Colosseum. While walking around the upper gallery, I was debating in my head whether or not to set a particular sequence in the ruins of the ancient amphitheater. In the midst of my hemming and hawing I turned my head and saw this stone Mantis face. So yeah, maybe the Colosseum will find its way into one of the novels.