One of the first times I recall seeing one was in the park down the street from my house. He was a boy, about my age—around ten at the time. I was crouched at the edge of the park, near the slope of a ravine. He came walking toward me. I had never seen him before. He asked me what I was doing and I pointed to a baby bird that was standing in the grass, stunned from presumably having fallen from its nest in the tree above. I told the boy I would watch it while he got some water and some grownups to help.

He ignored my suggestion and stared at the bird with a look in his eyes that made my skin crawl. It was an inhuman look, like the stare of a wild predator, a wolf or a panther. He then said in a cool tone that the bird needed to be put out of its misery. It was weak, he said, and a dog or cat would get it soon if we didn’t take care of it. I was confused by his statements and then I sensed danger radiating from him and my heart began to pound. He stepped toward the bird. I started to move in front of the animal, but I was too slow. His foot was already flying through air. I screamed as he kicked the bird hard, flinging it into the ravine.

I burst into tears. When I looked up at the boy he was laughing. A sick, evil laugh, and then he walked off. Shaken, I scurried down the slope in search of the bird, begging that it would somehow still be alive. It took me an eternity to find it and when I did, it was dead. I picked it up and carried it home, sobbing, and buried it behind my house.

In the weeks after this incident, two things haunted me. One, the guilt that I could have done more to save the bird. And two, the memory of the boy who killed the bird. The wolfish look in his eyes and that evil laugh.

During that summer I would see him once in a while in the park, laughing and playing ball with some friends. The sight of him made me sweat and pant and I stayed clear. I would eventually learn from another neighborhood boy that his name was Chris. I would continue to think about him a lot and worry about all the other birds or animals he was probably killing. He was different, different from me and any other boy I knew.

Some years later I would figure out that what made Chris different was that he had no conscience, that he felt absolutely no remorse for killing that bird. In fact, it gave him pleasure.

He was a sociopath.

He eventually moved out of the neighborhood, but every few years I would get wind of where he was, what high school he attended, what university he went to. A few years ago I learned through an old childhood friend that Chris had become an investment advisor and that he was charged with defrauding his clients out of millions of dollars. I later learned that he’d fled the country and was probably living somewhere in the Caribbean.

I have long wondered if Chris would ever end up murdering someone. Maybe he has, or still might someday, but—so I’ve learned in my reading on sociopathy—it’s equally possible that he’s not homicidal. Not all sociopaths or psychopaths are. But all of them are predators in some form, whether that means they steal someone’s business idea, emotionally torture a coworker, or parasitically live off a partner.

The more extreme and powerful psychopaths are the ruthless corporate sharks, the Ponzi schemers, the corrupt politicians, the mass murderers, the evil dictators that plague our world. They are the ones who make war, who sponsor genocides, who build the systems that separate the rich from the poor.

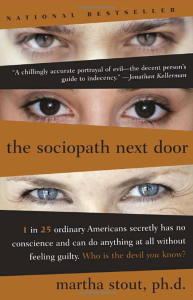

According to experts like Martha Stout, author of The Sociopath Next Door, one out of every 25 of us is a sociopath. While people like you and me far outnumber them, the sad truth is that this tiny minority is largely responsible—directly or indirectly—for making life on this planet at times painful, intolerable, unbearable, or impossible.

I recently read a Scott Adams quote—from The Dilbert Principle—that nailed this truth: “We’re a planet of nearly six billion ninnies living in a civilization that was created by a few thousand amazingly smart deviants.”

The sociopath has not only created the world we live in. They’ve written our entire history—our long history of oppressive regimes, of ceaseless war, of torture, persecutions, inquisitions.

I still frequently recall the look in Chris’s eyes as he worked out his plan to kill the bird. Every time I picture that psychopathic stare I get a shiver. That haunting image is one of the reasons why I’ve long struggled with the question of why the human race includes the sociopath. It’s also one of the major questions I’ve tried to explore in the Mantis trilogy, which features various antagonists including the Nazis of WWII, a cauldron of sociopathy.