Something melts inside me when I look at these photos. It’s hard to explain. I want to be there, inside the photos, inside the moment they were taken. To me, they are works of art, the seizing of some perfect second in time. The thing is, these are just ordinary photos—family photos my grandmother collected and saved in a box, one my younger brother inherited years ago.

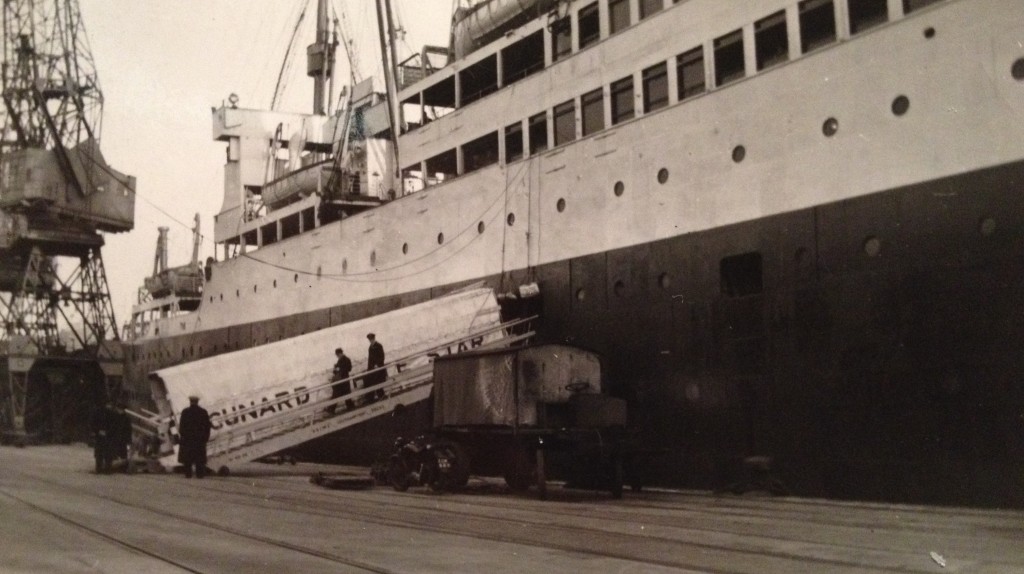

He brought the box with him when our family got together a few weeks ago to celebrate my mom’s birthday. Many of the photos were from the ’30s and ’40s and were probably taken in Scotland, and as I looked at them while we passed them around the dinner table, I was immediately pulled by these images into a magical place. A history that I admittedly romanticize. It’s almost impossible for me to imagine the reality that informed these pictures—to see the colors. The world in these photos is sepia-toned and exists beyond history. I know that the fear of the Depression or the terror of the war must have been there in these scenes, in the minds of the figures, the person—maybe my own grandmother—taking the photo. But still, it seems better there. There’s beauty in the simplicity of the machinery, the ship’s hull, the tackle and the cables, the physicality of the world—the absence of the digital, the abstract. Just hard steel and people.

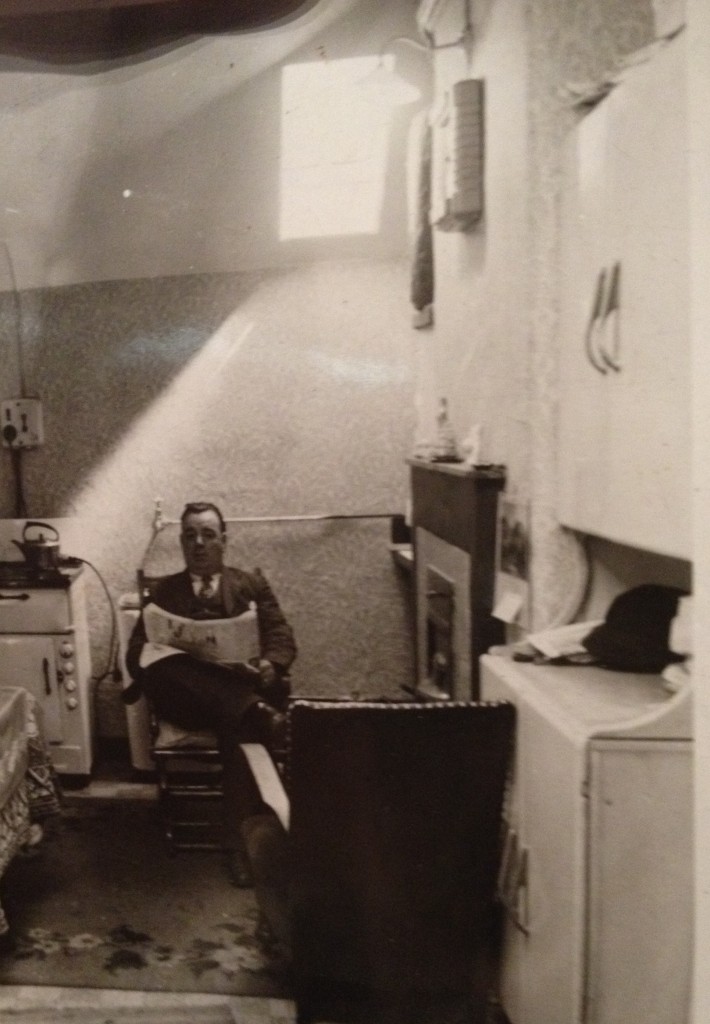

Below, my grandfather sits by a kettle on a stove, reading a paper.

I have no idea who the man in the hat is in the picture below, nor the woman overlooking the railing of the steamship. But it’s hard for me to believe that it’s a random family photo and not a stunning art photo intended to tell some deep story of the human experience—of separation, adventure, loneliness.

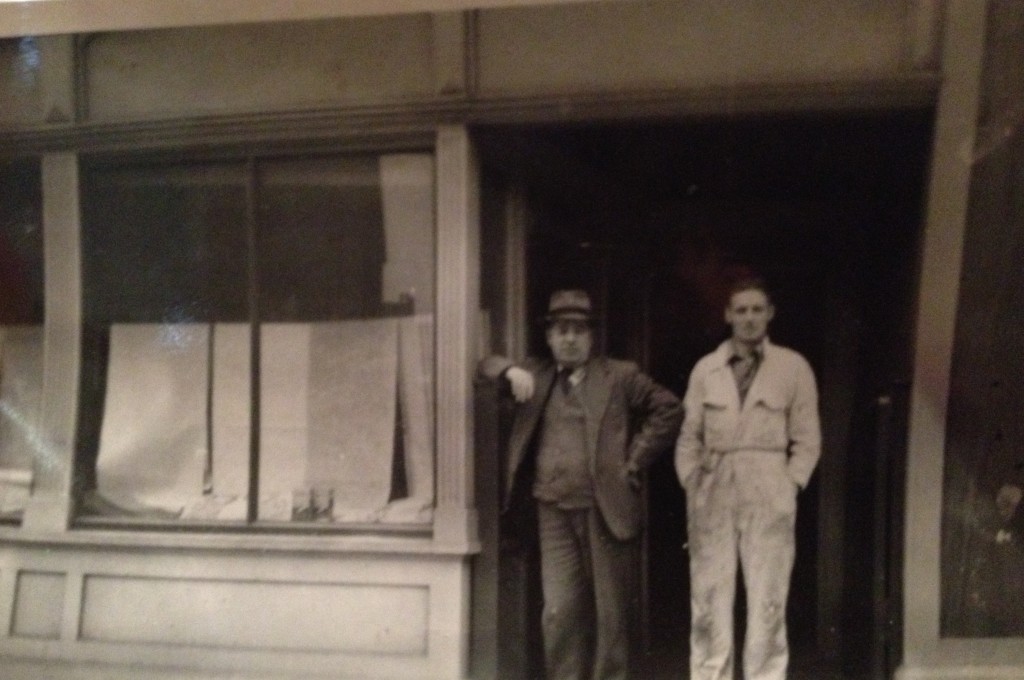

Or that this photo, of my grandfather and someone else in the doorway of what I believe to be his Depression-era shop, is just a random moment, and not an emblem of fortitude.

I grew up listening to stories of this time from my father. No doubt this lies behind my writing of a book about a man who lost his father to another time.